“Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; but what matters is to transform it.” The famous Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach by Karl Marx suggests that there is a clear difference between abstract theorizing and revolutionary action. The apparent opposition between reflection and action, between theory and practice, was retroactively reinforced in the version edited by Friedrich Engels, in which he added the word “but” to the sentence. Through an interpretive intervention he thus underscores the merit of action.

But is Marx truly concerned with the difference between philosophizing about the world and changing it? Or is he rather hinting that we should take philosophers at their word if we want to achieve the objectives they show us with their analyses? If our ultimate aim is the emancipation of all humanity, then we must try to find the inherent potential for liberation within the societal conditions, however difficult they may be at present, and “force them to dance,” as Marx writes elsewhere

And that is what this publication is about—with regard to a fundamental contradiction in contemporary society: the contradiction between the social character of production and the private appropriation of the results of this production. Specifically, it deals with the question of ownership of land and data, and the effects of these ownership relations on the production of space.

Who owns the land? This question is of crucial importance for all societies and their coexistence. This is because the availability of land and property controls the production of space and the social order. The fact that land (space) is as vital to life as air and water means that its use should not succumb to the unmistakable play of free (market) forces and individual whims.

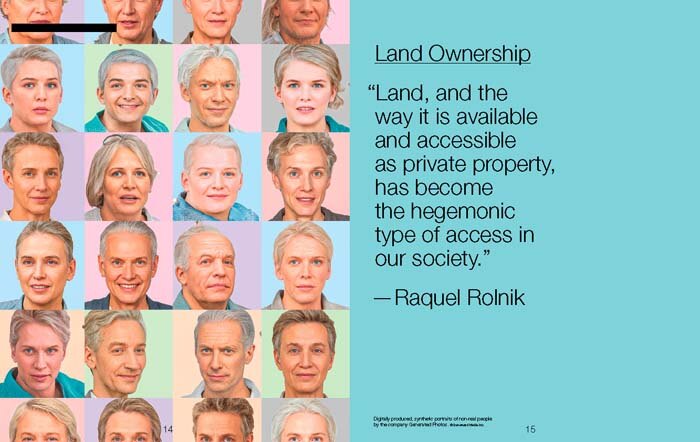

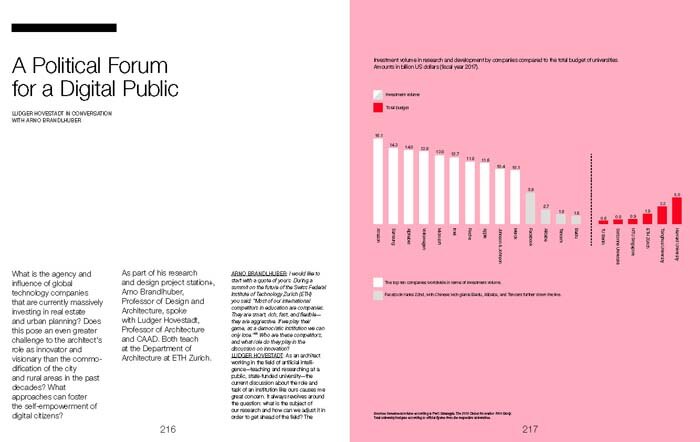

Who owns data? For urban planning, the issue of data ownership has become just as relevant as land ownership. In this issue we therefore discuss the politics of space and the politics of data, the real and virtual capital of the city of the future. The debate is guided by two main questions: How do we deal with space and data as planning resources? And what role do architects and urban planners play in the digital society?

The intertwining of land ownership and finance is by no means a recent invention. On the contrary, as the philosopher Wolfgang Scheppe explains in this issue using Venice as an example, it has always been part of the city’s feudal reality: “The limited space available for building in the city area, together with the huge and unprecedented concentration of consumers, gave the small number of aristocratic families—who had succeeded in transplanting liege conditions into the urbs—a likewise unprecedented monopolist position to increase the value of their real property. For this reason, Sombart sees ground rent as the ‘mother of the city’. […] He identifies the city’s major landowners, who divided up the city among themselves, as the real creators of the city.”

However, the example of Venice also shows that despite historical continuity, a radical change has occurred. Whereas landowners were once dependent on the population for generating ground rents, today the opposite holds true for the urban centers that draw tourists: the local inhabitants are an obstacle for those who seek to exploit the lands. Living space is seen as “unproductive” because it yields less than the income generated by festivals, biennials, and tourism. The consequence: the marketing of cities means the disappearing of city residents, who “underperform” in the global run on space as a resource.

What can we do about this? Not much, because there is no alternative but to politicize land. A lot, because so far everybody has failed to do so. But if we define the city as a commons for the whole of society, there is no way around comprehensive reform. It must begin with changing our conceptual orientation by denaturalizing land through a philosophy of land—by strengthening the understanding that land is always a cultural and social product, and therefore a political product (see the contribution by Milica Topalović). We must find sound arguments against the dogma of privatization! The idea of land ownership based on natural rights put forth by John Locke in the seventeenth century offers a point of attack. By linking property rights to the amount of work invested, Locke linked economic theory with political theory. This line of argumentation can be used to develop a political economy of the city, and to show that the current situation is anything but “natural.” The contributions in this issue reveal the prevailing lines of conflict, but also possible potentials to redefine property in order to make the city conceivable as a public good in the long term.

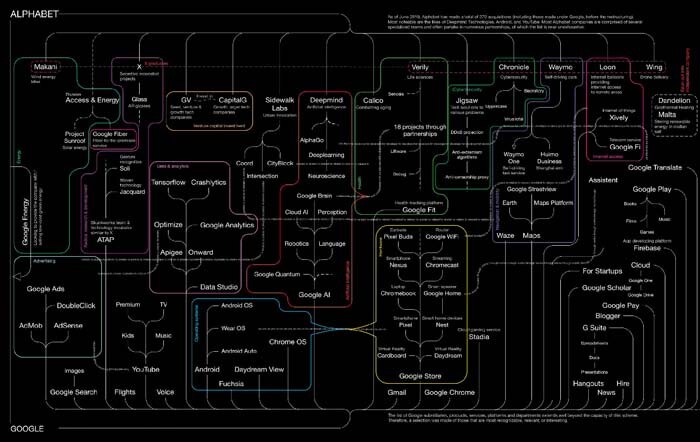

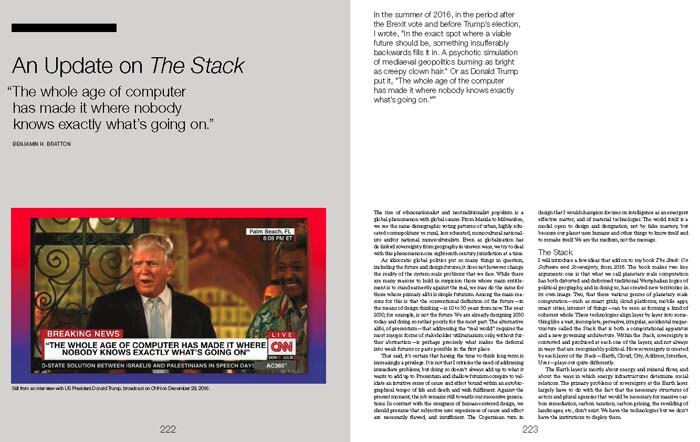

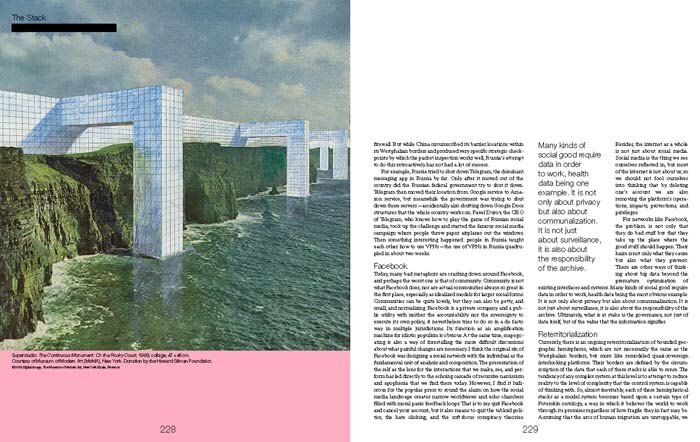

Despite financialization, digitalization, and virtualization, the use of space, an increasingly scarce resource, is becoming more critical than ever. Tech companies such as Google, Microsoft, Airbnb, and Uber have long since stopped contenting themselves with the commercialization of all social activities; now they are investing their stock market gains in real estate and land. Following their respective corporate logic, they have also begun to plan their own cities of the future. Take, for example, the Sidewalk Toronto project by the Alphabet/Google start-up Sidewalk Labs, which treats residents as sources of data. In the future, artificial intelligence will be used to regulate the distribution of space.

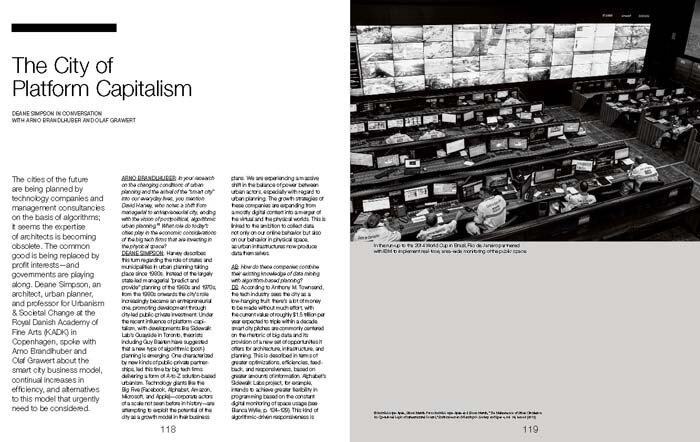

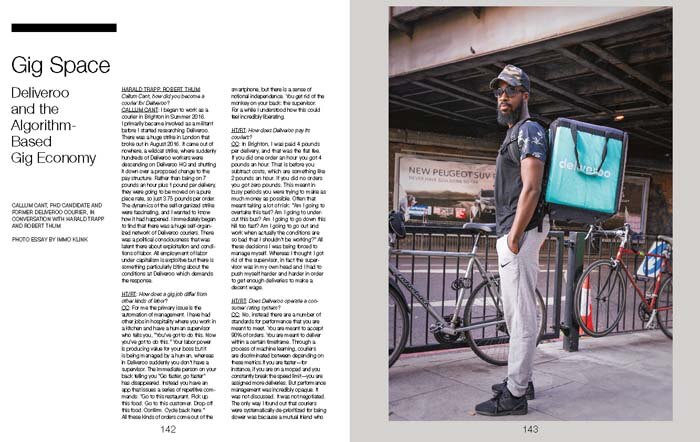

For architecture in particular, this development has far-reaching consequences. With the smart city discourse, algorithm-based planning methods, and massive investments in infrastructure, the tech industry is penetrating far into the field of architects and planners. Their technocratic visions turn citizens into users, says Christian von Borries in this publication: “First, architecture becomes an instrument of statistics and then provides information about user behavior. The role of the architect no longer exists in this scenario, or it is limited to the design of unconnected buildings in the urban space that are predetermined by algorithms.” Have architects in post-planning, as Deane Simpson calls this development, become obsolete?

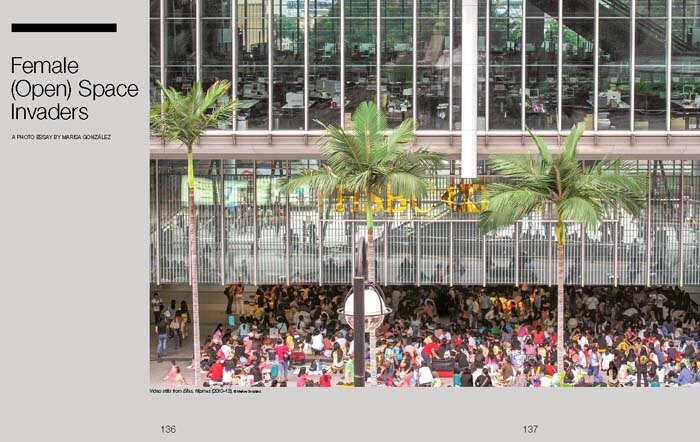

This issue clearly demonstrates the radicalization of economic thinking, with which the city is conceived of and produced as an exclusive space. Cities are becoming the tech industry’s central line of business, and their target group is the urban elite. This development is based on (user) data collected by the billions from mobile applications, from delivery and mobility services, and increasingly, from smart cities. The penetration of major tech companies into the physical space presents us with new challenges. After all, big data also enables new planning and design tools. However, the algorithms, equations, and conclusions behind these tools and applications are not unquestionable truths. They are neither neutral nor objective. Behind them are people—data analysts, programmers, and business people—whose decisions and interests shape our imaginations and our daily lives.

What does it mean for urban society when private companies increasingly assume the tasks of the public sector? What happens if cities thereby increasingly follow an entrepreneurial logic and the associated technocratic ideals of datafication? “Quantifying humans and habitats transforms them into biometric entities and streetscores,” warns anthropologist Shannon Mattern in her article. In this vision, Mattern continues, the city, society, and people are nothing more than “algorithmic assemblages.” The implications are thus not only to be found in our social interactions, but also in our self-image as human beings. The digitally produced, synthetic portraits of non-real people by the company Generated Photos on the cover are a dramatic demonstration of this insight. They are the result of machine learning in generative adversarial networks. These “random unreal people” are, in a sense, our avatars in an era of post-politics and post-planning. So the story is about us. De te fabula narratur!

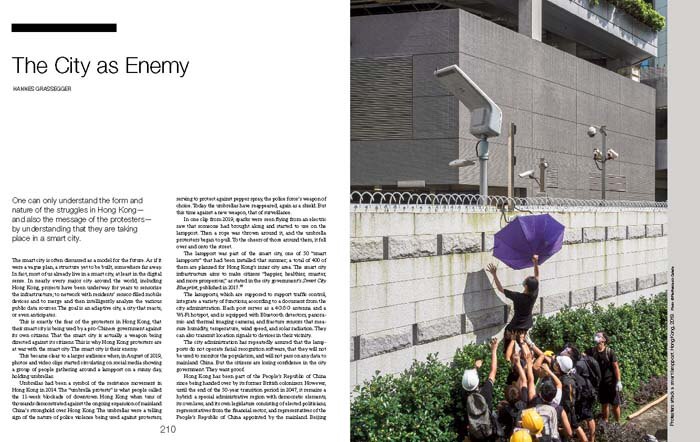

How can architects react to the unstoppable advance of the smart city and datafication? Not only in the gesture of resistance, as Hannes Grassegger impressively reports by example of the urban struggles in Hong Kong, but by making the phenomena, in all their contradictions, the subject of design and planning for an emancipated urban society. After all, if we Marx’s theory of self-creation seriously—that we create ourselves by being productive in society—architects and planners are in a key position to shape the social realm. We don’t have any other choice, either. We cannot rely on the fact that the system will destroy itself through its inner contradictions. Rather, like everything else, it evolves by actually playing out these conflicts and contradictions. It’s called dialectics.

Arno Brandlhuber, Olaf Grawert, Anh-Linh Ngo

+ + +

This publication was produced in collaboration with guest editors Arno Brandlhuber and Olaf Grawert (station+, D-ARCH, ETH Zurich) and ties in with the films Legislating Architecture: The Property Drama (2017) and Architecting After Politics (2018) by Brandlhuber+ and Christopher Roth. It summarizes the two German editions ARCH+ 231 The Property Issue and ARCH+ 236 Posthuman Architecture and supplements them with new articles.

+ + +

Editorial team ARCH+: Anh-Linh Ngo, Mirko Gatti, Christine Rüb. Guest editors: Arno Brandlhuber, Olaf Grawert, Angelika Hinterbrandner. Contributing editors and editorial assistants: Nora Dünser, Nils Fröhling, Christian Hiller, Max Kaldenhoff, Melissa Koch, Alexandra Nehmer, Alexander Stumm

C O N T E N T

| 00 Synthetic Portraits of Non-Real People 01 Editorial 06 The Disappearance of Architecture and Society in the Algorithm 14 LAND OWNERSHIP 16 The Ground-Rent of Art and Exclusion from the City 36 Land as Project 48 Land Policy Glossary 52 The Value of Land 60 “Property Entails Obligations” 66 Toward a New Land Policy 70 Capital Home 78 Land of the Free Forces 84 Defending Democracy 90 “The Public Sector is a Great Source of Freedom” 102 Into the Ground 110 Property without Obligations

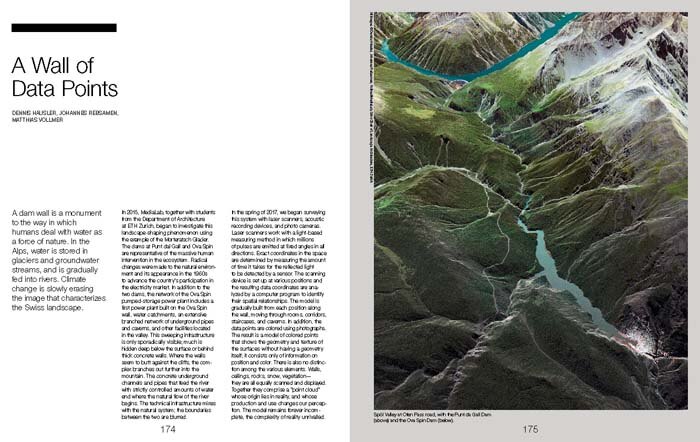

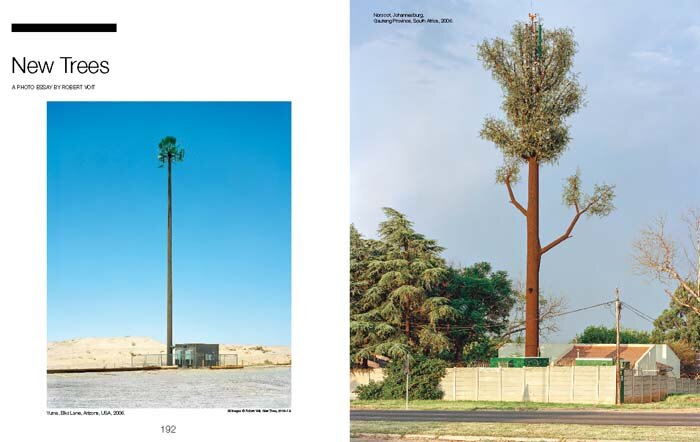

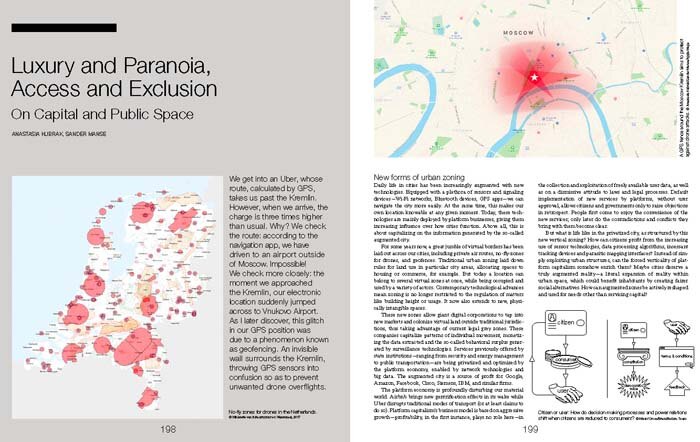

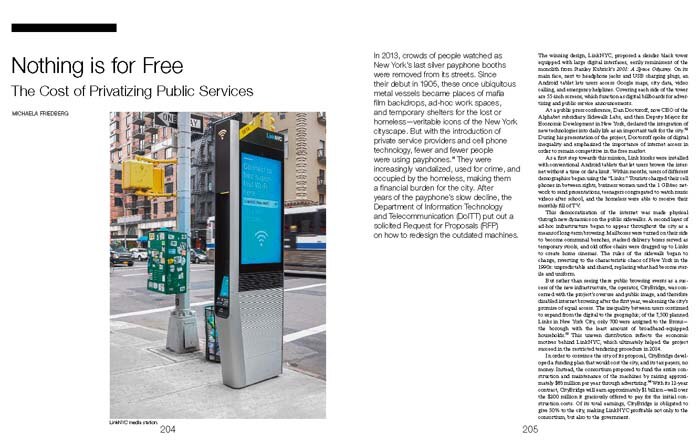

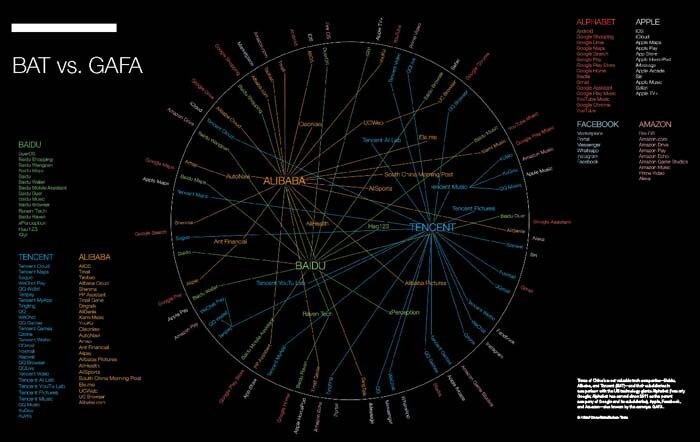

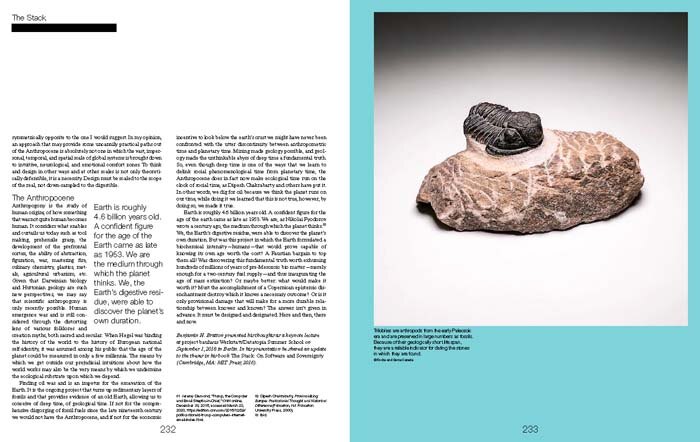

| 112 PLATFORM URBANISM 114 The Challenges of Platform Capitalism 116 Alphabet World 118 The City of Platform Capitalism 124 Searching for the Smart City’s Democratic Future 130 “The Architecture of Neoliberalism Disavows Labor” 136 Female (Open) Space Invaders 142 Gig Space 154 Platform Cooperativism 162 POLITICS OF DATA 164 Databodies in Codespace 174 A Wall of Data Points 184 Agency in the Age of Decentralization 192 New Trees 198 Luxury and Paranoia, Access and Exclusion 204 Nothing is for Free 210 The City as Enemy 216 A Political Forum for a Digital Public 220 BAT vs. GAFA 222 An Update on The Stack

|

Spring 2020

240 pages

International shipping will only be processed after receipt of payment; therefore we recommend to use PayPal.

Publishers:

ARCH+

ISBN 978-3-931435-57-8 //

Birkhäuser

ISBN 978-3-0356-2106-8

Buchhandelsbestellungen / Bookshop orders

via Birkhäuser/HGV

ISBN 978-3-0356-2106-8

available from 7th June 2020

birkhauser.ch